It’s not that I didn’t know what hip-hop was when I popped the disc for Jet Grind Radio into my Dreamcast (R.I.P.) that glorious day back in late 2000. I was a small-town, rural kid with no MTV in the house, but I was made plenty aware of rap. My friends made sure of it, even growing kid up in a household that didn’t allow the parental advisory sticker into its confines (at that age, at least). But it’s not something I really fought for all that much either, if I’m being honest, because pre-teen me didn’t understand the appeal of it.

Eminem, Busta Rhymes, Ja Rule, Puff Daddy, Jay-Z, DMX, Missy Elliott and Mystikal all sat in my consciousness. I’d nod along and have to confess to a certain obsession with “Party Up (Up in Here)” during basketball camp months earlier, but I didn’t consider myself much of a fan, regardless. Short of OutKast’s Stankonia — the Walmart-sold censored version of which sits somewhere in my closet — I didn’t care. I looked at rap as a different flavor of pop, and I wore my refusal to listen to pop as a badge of honor back then. That was dismissive (both toward rap and pop) and misguided, especially given how much substance so much of that possessed, but it doesn’t change the fact of the matter that I couldn’t connect to it. I couldn’t, and I didn’t bother to try. Stubbornness is what it was, and it would have to sneak into my system for me to give it an honest shot.

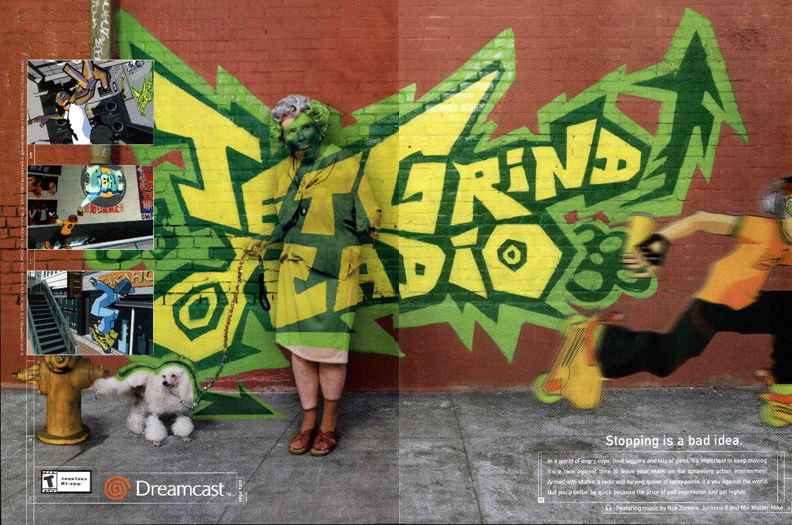

That’s exactly what happened. I would never have expected that a video game would be the thing to change my mind. I purchased my Dreamcast with my eyes set on Crazy Taxi, NFL2K and NBA2K, and I adored them all. It was later that I picked up Jet Grind Radio, intrigued by a premise and promising reviews. It’s such a niche game that was really outside of anything in mainstream gaming to that point. An immediate favorite (I still adore cel-shading even past its heyday), it was an exceedingly difficult experience to explain to my friends, let alone any adult figures in my life. In a nutshell, you play as Beat, fighting a turf war by traversing Tokyo on inline skates, tagging over a rival gang’s graffiti. Like, what? But it’s great, and combating The Love Shockers, The Noise Tanks and Poison Jam with a can of spray paint is some of the most fun you’ll ever have. There’s a beauty in the simplicity of the gameplay and colorful graphics, and hot damn did I get high on it.

I didn’t love the game for the parallels it held in my life. It had none. Not a single one. I was drawn to it for how polar opposite this world was to my existence, and the music — blending funk, trip-hop, soul, turntablism, electronic, J-pop, acid jazz and, inexplicably, metal in the American version — was a massive part of that sensation. It immersed me into a world I’d only seen the very fringes of in magazines and on TV, to the point where it was a totally alien experience. Intoxicating, but not necessarily overwhelming, the neon buzz and urban-centric art was given a universal center of gravity with the soulful samples and production that coursed through the soundtrack. It shed a new light on jazz; funk didn’t feel dusty anymore; it awoke the elements I treated as belonging to the past and made them feel more vital than anything I’d experience thereto.

And I played the game for that feeling as much as I did to finish each mission. Video game composer Hideki Naganuma absolutely kills it with throwback “Humming the Bassline” and “That’s Enough,” as does B.B. Rights on “Funky Radio,” Richard Jacques’ entry “Everybody Jump Around” and Feature Cast with “Recipe for the Perfect Afro.” The American release (the Japanese was originally titled Jet Set Radio) included cuts by Mix Master Mike, O.B. One and Jurassic 5. That last name is the important one, at least in my journey. That was my point of entry into something more tangible, a real-life entity that gave me a diving board to jump into the deep end.

De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest were names I’d seen in the pages of Spin, but they meant nothing to me — might as well been a list of past vice presidents. But now … now, I had to know. I nabbed J-5’s Quality Control (and Power in Numbers a few years later), De La Soul Is Dead, The Low End Theory — it was the dawning of an understanding. Soon after came Gang Starr, The Roots, Mos Def and Black Sheep (I have NBA Street to thank for that one), and all of a sudden, hip-hop made total sense to me. Retroactively, I could see Jay-Z in a new light. Kanye West, Gnarls Barkley, Lupe Fiasco, The Cool Kids and Clipse became some of the artists I was most excited about in the year’s to follow, something that Danny Brown, Odd Future, Action Bronson, Kendrick Lamar and Joey Bada$$ have served to renewed over the past few.

Granted, it was three-prong attack. Gorillaz broke up a short year later (a late-night viewing of the video for “Clint Eastwood” is the most enamored I’ve ever been), N.E.R.D.’s In Search Of … came the year after (play “Rock Star” at my funeral, please), and I have little doubt that either one would have jumpstarted the same self-discovery. It was inevitable. But it wasn’t those things; it was Jet Grind Radio. I just needed a glimmer of the other side, I think, to make me welcome the entirety of it, and it happened to be a video game that properly introduced me. Game over.