The Thin Blue Line

Director: Errol Morris

(Blu-ray/DVD)

A

Documentaries are odd, contrarian beasts. Arguments are often made to suggest that film really only provides an avenue for escape. But movies more often make us out to be satellites; we are usually far enough to be safe, yet close enough to cry. They can yield an emotional upheaval so intense and brief that it resounds at just the right frequency, as to not spoil the ride home. So is it not odd that one particular genre, documentary, strives to pull us from orbit and set our vessel ablaze?

Seasoned documentarians can meld a strong dose of reality with an unparalleled experience. Such is the case in The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris’ opus-worthy film examining the frailties of authority, bureaucracy and testimony. But more important is its uncanny ability to mesh near-objectivity with superb storytelling, thus conveying a tale as beautiful and important as it is jarring.

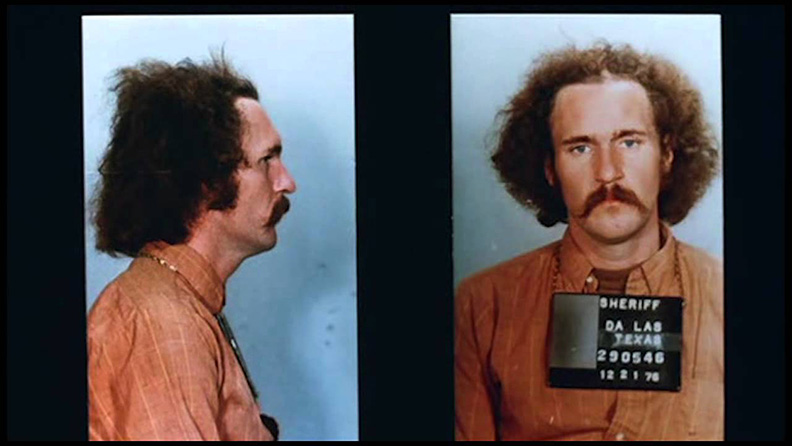

The film centers on the case of Randall Adams, a man convicted of murdering a Dallas police officer in 1976. Though seemingly straight forward, Adams’ story was far more intricate, as he was ultimately proven innocent shortly after the movie’s release. After running out of gas on his way home from work, Adams is picked up by runaway teen David Ray Harris on an evening in late November. As many of Morris’ subjects would contend, the truth of the affair remains elusive.

Most compelling, though, is the fact that the film was made without any explicit notion of Adams’ innocence. Morris’ subjects are given breathing room, which allows the narrative to readily transcend Adams’ tale. Instead, an examination of justice, culture and the misanthropic quirks embedded within American life is put forth seemingly unprovoked.

Despite a liberal dissection, The Thin Blue Line never meanders. Interviewees come from nearly every corner, covering everything from Adams’ supposed evil nature to the racial divide of the penal system, but the discourse carries a natural depth and complexity synonymous with life.

The frame and tethers that Morris does weave are exceptionally crafted. Reenactment is the filmmaker’s primary vehicle, yet they are done so in a way unmatched by the vast majority of both contemporary investigative programs and even crime dramas. Silhouettes glide across the screen, and the pivotal incident is retold several times over, each time with an invigorating twist — similar to the evolving perspectives of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon. Morris surgically and momentarily shines a light into each of the film’s bleakest crevices, leaving room for one the most prevalent human constants: doubt.

Despite Morris’ apt construction, The Thin Blue Line wouldn’t achieve such cinematic heights without Phillip Glass’ score. Not unlike George Tipton’s work for Terrence Malick’s Badlands, Glass conveys echoes of wonder trailed by anxious whispers. Its frequent chimes toe the line between indications of innocence and desperate fabrication, never lending itself to one particular side of the narrative. His score is largely soft but always in a state of growth, as if to hint at a veiled but potentially momentous secret.

Over 30 years removed, The Thin Blue Line is still undeniably impactful. Morris’ masterpiece works in its ability to meld thematic dimensions; it’s never explicitly about a murder, nor a governmental flaw. An anomaly in any regard, the film is somehow both critical and empathetic. It’s both a period piece and a timeless discourse. It’s quaint yet progressive. Humble yet brilliantly dauntless.